THE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT

By Günter Dollhopf

Fritz Hagl in the 60s.

Therefore, only the fact that I am not an art historian affords me the chance to write about his work today and to represent the value of his paintings. Being a painter myself, I had the good fortune to have been able to follow Hagl’s work over the course of many years, with a partly critical, partly encouraging and admiring friendship.

From 1970 I visited regularly, yearly, his studio on the island of Elba, and therefore I was able to, at least partially, follow the evolving process of production. I am less concerned here with historical/stylistic comparisons but rather with the creative contexts of origination.

Because artists are entitled to the privilege of ego-centricity, I (being an artist myself) dare to employ a subjective view, based on my own visual thoughts and actions. Only from a personal viewpoint such as this is it possible to find an approach to Hagl’s paintings, because throughout his life he stead-fastly refused to be subjected to “objective” comparison. He never exhibited his work in public, with one exception in 2001. With the awareness that painting is the grand design and mission of life, he withdrew from art commerce, with inner conviction and a sense of necessity.

Thus he realized Dürrenmatts claim, who demanded (in a speech on the occasion of being awarded the Bern Prize for Literature 1979):”Whoever does not care in time to move out of the cultural gossip zone, will not be able to truly work again and therefore not get to the core of his self). And this should actually be the goal of our labor, rather than reaching some height of literary fashion. Only the one who came into his own being, will be able to fulfill the task: to cope with the world, to provide it with self-determined meaning”.

The power of Hagl’s personality was totally based upon his reliance on the direct energy of his paintings and not on their placement in a scene. Of course, his attitude isolated him in this end of the twentieth century-world of merciless self-representation.

It is an oeuvre of impressive consequence and completeness, its magical content pointing towards other, deeper levels of being. “I am painting for God”, Hagl once said to me, when I asked him during the mid-seventies about the reason for his denial of public contact. Only now, after the social-political turmoils of those years have died down, is it possible to understand the meaning and sense of this astonishing answer.

The early works: 1958-1974

The first painting that I saw from Hagl’s was a portrait from 1958: a man with a hat, green scarf, bluish-black jacket, and a bit of a forward stoop, looking at the viewer; the crossed hands with brown shadows and glaring lights are leading diagonally to the lower right. Such portrait studies seem to always stand at the beginning of an artistic career. So it is that I also tried hard with this kind of efforts in the beginning of my study period. In my frustration at the time I failed to recognize the artistic qualities of the painting and the special human expression in the face of the painter’s model.

Fritz Hagl, N.T. 1964, Pen and ink, cm: 40 x 30 (Abb. 2).

At first, Hagl had built his house on Elba, between 1960 and 1983, drawing in-between and afterwards. Only after the installation of his studio was he able to aim at long-term painting projects.

The tempera landscapes developed from 1965-70 appear to be more abstract, farther away from nature compared to the drawings created outdoors.

In the “ideal landscapes” one can detect the representation of mythical ideas, which express itself in special ways of re-arranging natural forms in the portrayal of strangely stylized human beings that inhabit the utopian rock formation.

The middle years: 1975-1988

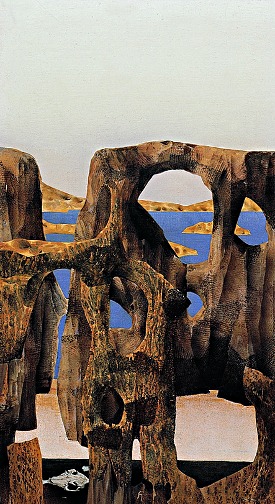

Fritz Hagl: N.T. 1976, Tempera on canvas /

pressboard, cm: 61 x 36,5 (Abb. 4).

pressboard, cm: 61 x 36,5 (Abb. 4).

Next to several middle-size formats on the walls of the studio there is a small painting on the easel, depicting the sea, the sky and rocks. There is evidence of a technical and artistic mastery, which from then on is constantly realized in Hagl’s paintings. All patterning, rigidity, underdevelopment is gone and makes room for a new artistic direction.

There is an expanded conception of form, an altered sense of reality, connected with clear and light expressions of color, which lends a new power of projection and life to these new paintings.

Equally engaging in these new paintings is Hagl’s invention of a special scaling of space: he moves scenes of boulders or human and animal bones in front of meticulously crafted parts of landscapes of sea and mountains. The folding of form elements, structured in two or three levels, is cross-connected in such a way that it can be read as a compact, close-circuit weaving of space. In and between these formations there are cave-like curves opening up, oval or other shaped form-openings, which clear the way to landscapes and seas like sea-through or break-through holes.

All of this is visually organized in such a way, that one experiences the reverse of the usual experience of space. The scenery in the foreground optically steps back by way of shadowing techniques, and the lighter forms in the background push forward into the foreground as “see-throughs”. Both planes are thus meeting on the same optical level. Hagl succeeds in bringing together parts in terms of perspectives of space do not belong together; a common presence despite the difference of distances; a simultaneity of the non-simultaneous.

This continuity of presence creates an aura of meditation, a feeling of time standing still.

These paintings are of a dream-like beauty. They transmute forms of visible reality and lead into a visionary world of images. Perhaps their secret is hidden in that shift of space and time described above.

As art history tells us, there have been other artists that worked with similar ideas of space scaling and the structuring of “negative” form elements. Paul Cézanne and Max Ernst are two that come to mind.

But in Fritz Hagl’s paintings there is a further step: “negative” form elements are treated full-scale like images within the image.

The close contact to the Elba nature contributes a special characteristic. These “concetti” become the constantly returning surprises in each new painting, and despite his definite tendency towards strict structuring and thoughtful composition his approach always feels lively, because Hagl, by observing nature, arrived at all organic form elements, which grew stronger as the years went by.

Another feature of Hagl’s compositional technique is the “holding on to the lines”, connecting contours as a linear weaving throughout the entire painting. Beings or objects are not isolated in the square of the painting, but are woven together as a grand ornament. He discovered this concept in the late seventies, while studying the works of ancient masters. It becomes the governing way of structuring the paintings in his late period. “Look how the lines are running through”, he said me once, while we were looking at a fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli in Florence, as his hand moved through the air.

The late work: 1988-2001

While human figures and images of animals had occasionally been woven onto the paintings, now, as of 1989, all figures leave the scene and a thoroughly braided wall of rock formations and vegetative elements is growing, filling more and more the entire formats.Hagl now works with very variated techniques, with the highest measure of precision. In a small workshop in front of the house he prepares his fundaments for the paintings in a lengthy procedure, just like the old masters. This is part of Hagl’s philosophy of life: he created his paintings like “a gardener who lays out his garden”, from the careful nurturing of the earth to the harvest.

After 1989 the painting areas grow rampant with porous rocky walls, which close the spacious depths. They are reminiscent of the rocks at the beach of Nisporto, but also remind me of photographs taken from a high distance above.

Hagl is no longer satisfied with single paintings. He paints groups of 3, 4 or 6. All illusion of perspective into the background is blocked. The stone structure are sitting right in front of us, as if painted on sheets or curtains. These structures present themselves on miniature spaces in a very distinguished way, and they show the whole richness of Hagl’s art in tiny cells. Micro and macrocosm are reunited. The detail radiating the same intensity as the finished work. I can still see Hagl cutting passe-partout of various shapes and sizes, out of card, so he could examine his paintings in every possible detail.

In his last, unfinished, painting Hagl returned to the wide , deep spaces, as if the walls that enclose the horizon had fallen away. The sky, the sea and the coastline appear once more as vast spaces; the cliffs are already finished , the blue expanses of sky and sea only planned in their structure and colors.

The way to the future has yet no answer.

(Translation Karl Hans Berger, musician)